Shin Splints

Benefits of Stretching after Workouts

May 18, 2016

Muscle Energy Techniques – Soft Tissue Release

July 10, 2016The term “shin splints” has been used by health care practitioners and athletes to describe any form of lower leg pain as a result of running. In truth, it encompasses three different conditions: chroniccompartment syndrome (CECS), medial tibial stress syndrome, and a stress reaction or stress fracture. A specific diagnosis is crucial, as they require markedly different treatment regimes.

CECS is a result of increased pressure in one of the four compartments of the lower leg (anterior and deep posterior are the most common, followed by lateral and superficial posterior), producing a gradual tightness and burning that quickly impairs the function of the muscles in the affected compartment and may produce numbness in the foot. If activity is ceased, the pain subsides in a matter of minutes, but the compartment in question may remain turgid to the touch.

CECS is a result of increased pressure in one of the four compartments of the lower leg (anterior and deep posterior are the most common, followed by lateral and superficial posterior), producing a gradual tightness and burning that quickly impairs the function of the muscles in the affected compartment and may produce numbness in the foot. If activity is ceased, the pain subsides in a matter of minutes, but the compartment in question may remain turgid to the touch.

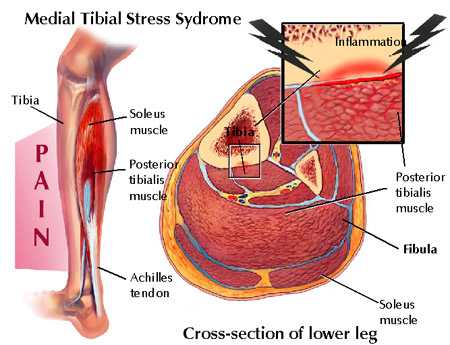

Medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) occurs from repetitive muscular pulling at the tibia. Pain usually occurs in the bottom 1/3rd of the tibia along the inside margin, and is very tender to touch. The condition may progress to the point where the tissue over the inside of the tibia feels doughy and becomes malleable to the touch. If left untreated, MTSS may progress into a stress fracture of tibia. This is the most common stress fracture in runners, and is described as a focal area of exquisite tenderness along the front aspect of the tibia. There may be night pain associated with this injury as it progresses, and naturally it causes pain during running. Sufferers generally complain of an aching, throbbing or tenderness along the inside of the shin (although it can radiate to the outside) about halfway down or all along the shin from the ankle to the knee. The pain associated with this condition is most severe at the start of a run but can go away during the run as muscles loosen up. Beginning runners are particularly susceptible to this injury as they often increase their mileage and intensity of training too soon. Usually, this causes over stressing of the lower leg muscles and their fascial connective tissue and is often combined with a poor choice in footwear. Runners who resume training after a long lay-off are also prime candidates.

Medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) occurs from repetitive muscular pulling at the tibia. Pain usually occurs in the bottom 1/3rd of the tibia along the inside margin, and is very tender to touch. The condition may progress to the point where the tissue over the inside of the tibia feels doughy and becomes malleable to the touch. If left untreated, MTSS may progress into a stress fracture of tibia. This is the most common stress fracture in runners, and is described as a focal area of exquisite tenderness along the front aspect of the tibia. There may be night pain associated with this injury as it progresses, and naturally it causes pain during running. Sufferers generally complain of an aching, throbbing or tenderness along the inside of the shin (although it can radiate to the outside) about halfway down or all along the shin from the ankle to the knee. The pain associated with this condition is most severe at the start of a run but can go away during the run as muscles loosen up. Beginning runners are particularly susceptible to this injury as they often increase their mileage and intensity of training too soon. Usually, this causes over stressing of the lower leg muscles and their fascial connective tissue and is often combined with a poor choice in footwear. Runners who resume training after a long lay-off are also prime candidates.

Injury to bone includes an array of defects in the architecture of bone from bone strain to stress reaction to non-displaced stress fracture to displaced stress fractures. Essentially, these injuries occur when bone fails to remodel adequately with the application of repetitive subthreshold stress. Due to the increased repetitive ground reaction forces in jogging and running, distance runners and track athletes are particularly prone to developing stress fractures. Ground reaction forces are three to eight times greater in jogging and running when compared to walking (Hoch, 2005). Stress injury of bone is the result of excessive bone strain with accumulation of microdamage and inability to keep up with appropriate skeletal repair (fatigue reaction/fracture), or depressed bony remodeling in response to normal strain (insufficiency reaction/fracture). Frequent sites of stress fractures in runners are tibia, metatarsals, fibula, navicular bone and the femoral neck.

Injury to bone includes an array of defects in the architecture of bone from bone strain to stress reaction to non-displaced stress fracture to displaced stress fractures. Essentially, these injuries occur when bone fails to remodel adequately with the application of repetitive subthreshold stress. Due to the increased repetitive ground reaction forces in jogging and running, distance runners and track athletes are particularly prone to developing stress fractures. Ground reaction forces are three to eight times greater in jogging and running when compared to walking (Hoch, 2005). Stress injury of bone is the result of excessive bone strain with accumulation of microdamage and inability to keep up with appropriate skeletal repair (fatigue reaction/fracture), or depressed bony remodeling in response to normal strain (insufficiency reaction/fracture). Frequent sites of stress fractures in runners are tibia, metatarsals, fibula, navicular bone and the femoral neck.

Potential Causes

- Tired or inflexible calf muscles which then put too much stress on the tendons.

- Over-pronation aggravates the problem.

- High percentage of hill running

- Running on hard surfaces.

- Dramatic changes in training regimes and/or training surfaces.

- High training volume is a major risk factor in stress fracture development.

- Abrupt or rapid changes in duration, frequency, or intensity of training programs also increase an athlete’s risk of stress fracture.

- Athletic footwear is designed to reduce impact on ground contact and provide stability by controlling foot and ankle motion.

- The surface on which an athlete trains also may contribute to her risk of stress fracture.

Treatment

For CESC and MTSS a reduction training volume is required. It is recommended that the running surface be changed grass or trails. Avoid hills and focus flat surfaces, especially in the early stages of recovery. If the condition is allowed to worsen as the runner tries to ‘run through it’, rehabilitation will take longer. Many runners mistakenly think that because the pain subsides after a mile or so, they can continue to train at the same level. Most learn the hard way that this only prolongs the injury. Ultrasound and anti-inflammatory medications can help reduce inflammation if the condition is not responding to regular icing and rest. A combination of joint manipulation, rehabilitative exercises, myofascial release therapy and/or Graston technique are for recommended for the conservative management of these conditions. If conservative therapy fails a surgical intervention is recommended.

Stress Fractures Phase 1 includes cessation of painful activity, ice, analgesics, maintaining fitness by cross- training, modification of risk factors, and possible bracing or electrical stimulation (Brukner, 2001; Verma, 2001).

Phase 2 consists of light-weighted exercises and nonimpact-loading activities, such as walking, using a stair stepper, elliptical, or cross-country skiing machine. Activity should resume slowly and increase by 5 to 10 minutes per day up to 45 minutes. If any bony pain occurs, activity should stop for 1 to 2 days and restart at a level below which the pain occurred (Brukner, 2001; Verma, 2001). Recovery of strength that is lost during phase 1 also should be addressed. Sport-specific muscle rehabilitation also may be started.

Phase 3 is gradual re-entry into the athlete’s sport-specific activity, starting every other day and gradually progressing to normal activity. This program may take from 3 to 18 weeks, depending on the extent of the injury (Verma, 2001). All athletes also should have a biomechanical and gait evaluation to assess for leg length abnormalities, excessive pronation or supination, pes planus, pes cavus (flat feet or high arches), and other structural abnormalities following a stress fracture.

All of the above treatment methods are provided by Dr. Janine McKay at DISC

Prevention and Rehabilitation

- Undertaking specific exercises to stretch and strengthen tendons and muscles in the front of the leg are the best way to prevent the injury developing and also to prevent it from recurring.

- Cross-training by swimming, biking in low gear, running in deep water, are good alternatives if you are forced to cut back your road training.

- Avoid over-striding, which puts additional stress on the muscles in the lower leg.

- Check that your running shoes are giving the support and cushioning you need.

References

Brukner P. Exercise-related lower leg pain: bone. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32(3 Suppl): S15– 26.

Hoch ZA, Pepper M. and Akuthota V. Stress Fractures and Knee Injuries in Runners. Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics in North America. 2005;16: 749-777

Verma RB, Sherman O. Athletic Stress Fractures: Part I: history, epidemiology, physiology, risk factors, radiography, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Orthop 2001;30(11):798–806.